Archaeologists in Türkiye have made a fascinating discovery—an almost 11,000-year-old statue that seems to depict a giant man holding his penis, alongside a life-size wild boar statue. These remarkable sculptures were found at the Gobekli Tepe and Karahan Tepe sites, which are among the world’s oldest temple sites.

The wild boar statue, carved from limestone and dating back to 8700 B.C. to 8200 B.C., measures 4.4 feet (1.4 meters) long and 2.3 feet (0.7 meters) high. Archaeologists detected pigments on its surface, suggesting it was once painted.

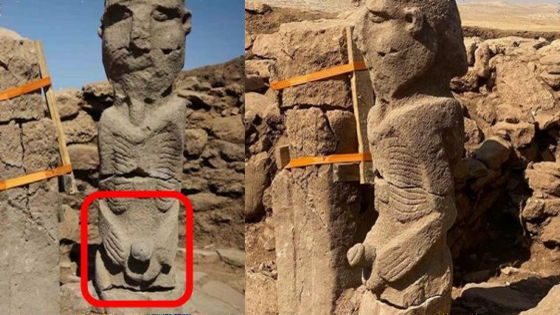

The life-size statue of a man, discovered at Karahan Tepe, stands at 7.5 feet (2.3 meters) tall. The sculpture portrays pronounced ribs, spines, and shoulders, hinting at a possible representation of a deceased individual.

These findings are the latest additions to the remarkable discoveries from Gobekli Tepe and Karahan Tepe, sites that have been reshaping our understanding of pre-agricultural communities.

Researchers, including anthropologist Benjamin Arbuckle from the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, note that these discoveries challenge previous notions about the simplicity and small scale of hunter-gatherer communities around 11,000 years ago.

Gobekli Tepe, known for its megalithic structures and intricate sculptures, provides insights into early human rituals, possibly funerary in nature. The presence of such sophisticated complexes challenges the notion of primitive hunter-gatherer societies and suggests a more organized and complex social structure.

The purpose of the newly found sculptures remains unclear. The statue of the man from Karahan Tepe is particularly intriguing. While interpretations are speculative, some suggest that the figure, potentially representing a significant ancestor, might be associated with the building where it was found.

The pose, with the figure clutching its penis, could symbolize the progenitor of a social group, such as a lineage or clan linked to the structure.

Ted Banning, an anthropology professor at the University of Toronto, suggests that structures at Karahan Tepe and Gobekli Tepe might have served as houses rather than temples. In such a context, each structure having its own lineage ancestor, as implied by the statues, makes sense.

The discoveries continue to unveil the complexity and richness of ancient cultures, challenging preconceived notions and prompting further exploration into the mysteries of Türkiye’s archaeological sites.