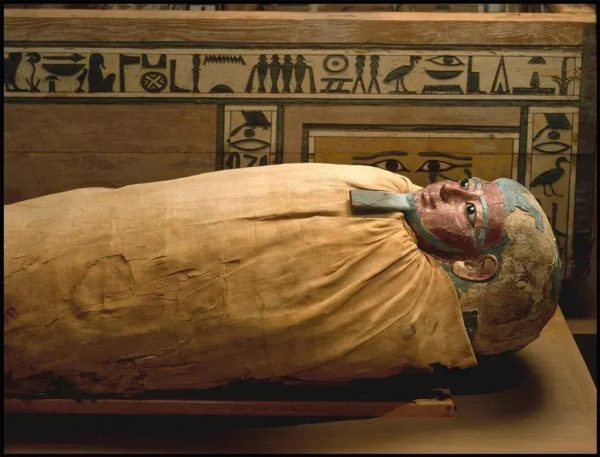

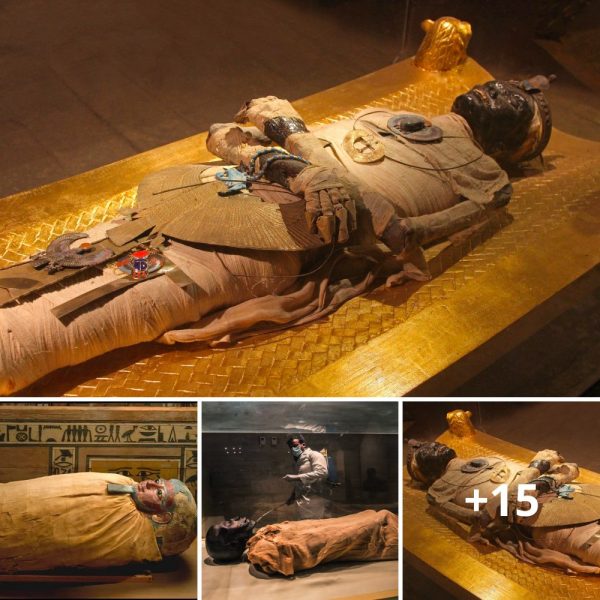

Egyptian mummification is a process that involves removing all moisture from the body, leaving behind a dried form resistant to decay.

The process begins with priests inserting a hook through a hole near the nose and pulling out part of the brain. Then, a cut is made on the left side of the body near the abdomen to remove all internal organs, which are left to dry.

Finally, the lungs, intestines, stomach, and liver are placed inside canopic jars – alabaster jars seen in many Egyptian museums. This process, a dark art with many secrets, continues to fascinate us today.

In Ancient Egypt, the Priests used Four Alabaster Jars for the dead king’s organs. The first one had a human head, carrying and protecting the liver, called Imsety.

The 2nd jar had a falcon’s head, carrying and protecting the intestines, called Qebehsenuef. The 3rd jar had the head of a baboon, carrying and protecting the lungs, called Happy. The last one had the head of a jackal, carrying and protecting the stomach, called Duamutef.

All are located at The Museum of Cairo, some of the King’s Mummies were located in The Mummy Room at The Egyptian Museum, while the rest are still at the Valley of the Kings, all in a good state of preservation.

An analysis of the residue on ceramics found in an ancient embalming workshop has given us new insights into how ancient Egyptians mummified their dead.

Even more astonishingly, a team of scientists has been able to link different substances to the specific parts of the body on which they were used.

This discovery is, in part, thanks to the residues themselves, which were studied using biomolecular techniques; many vessels were intact, including not just the names of their contents but instructions for their use.

“We have known the names of many of these embalming ingredients since ancient Egyptian writings were deciphered,” says archaeologist Susanne Beck of the University of Tübingen in Germany. “But until now, we could only guess at what substances were behind each name.”

And there was the workshop, filled with ceramic jars, measuring cups, and bowls, neatly labeled according to their contents or use.

Led by archaeologist Maxime Rageot of the University of Tübingen, the researchers conducted a thorough examination of 31 of these vessels, using gas chromatography-mass spectrometry to determine the ingredients of the embalming materials therein.

The detailed results are fascinating, and in some cases, completely unexpected. “The substance labeled by the ancient Egyptians has long been translated as myrrh or frankincense. But we have now been able to show that it is actually a mixture of widely differing ingredients,” Rageot explains.

Cedar oil, juniper or cypress oil, and animal fat were ingredients. The team found that the mixture may vary from place to place and from time to time.

The team also compared instructions inscribed on some of the vessels to their contents to determine how each mixture was used. Instructions included “to put on his head,” “bandage or embalm with it,” and “to make his odor pleasant.”