King Solomon’s famed mines, said to have accumulated a colossal amount of wealth worth more than £2.3 trillion ($3 trillion), are considered a legendary treasure trove from ancient times. The Old Testament speaks of Solomon being in possession of 500 tons of pure gold from mines that some believe are still in existence, alongside precious metals.

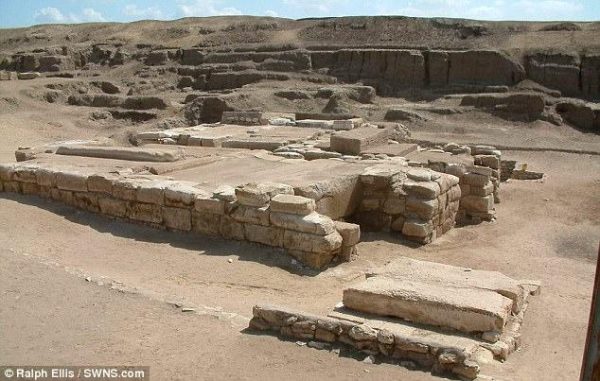

However, the veracity of King Solomon’s incredible riches has been a subject of debate among historians. Some argue that Solomon was not even the king of Israel but an Egyptian pharaoh whose reign has been misinterpreted. British historian Ralph Ellis suggests that Solomon was, in fact, a Pharaoh called Shoshenq I, ruling Egypt and Israel in the 10th century BCE.

Ellis contends that the tales of Solomon’s lost mines are as fantastical as finding a fountain of youth, with the legendary riches possibly being a gross misinterpretation of historical texts. He maintains that there is a significant misalignment between biblical accounts and tangible evidence, questioning the accuracy of accounts portraying Solomon as a wealthy ruler.

Furthermore, Ellis challenges conventional beliefs by suggesting that Solomon’s treasures could be more symbolic than literal. He infers that the biblical narrative may be an exaggeration or a reflection of the political and cultural motivations of the time, rather than a precise historical record.

Despite the existence of archaeological finds such as ancient gold artifacts discovered in Jerusalem, the specifics of Solomon’s mines remain a mystery. The novel by Rider Haggard, “King Solomon’s Mines,” fueled endless speculations into Africa, Arabia, and Asia but lacked universal acceptance of the validity of Ophir’s gold discovery accounts.

Demonstrating a divergence in historical accounts, Ellis posits that Solomon and his father David were actually Pharaohs Psusennes II and Shoshenq I, respectively. He delves into how even the genealogies and family members associated with these two royal dynasties appear to align perfectly.

Ellis emphasizes the need to consider these “Israelite” kings were purportedly Pharaohs of Lower Egypt, shedding light on the inconsistencies within the biblical narrative. By accepting that these “Israelite” rulers were part of Lower Egyptian history, the discrepancies in biblical accounts become more explicable.

In conclusion, the legends surrounding King Solomon’s mines continue to captivate the imagination, but the historical accuracy remains shrouded in uncertainty. Ellis’s alternative interpretations challenge preconceived notions and invite a reassessment of ancient history through a different lens.