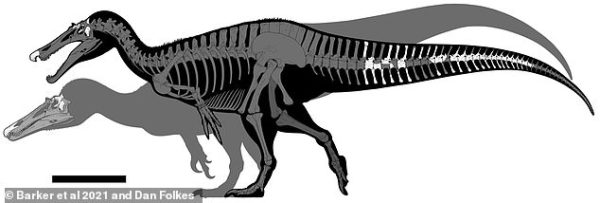

Scientists from the University of Southampton have recently shed light on the evolution of semi-aquatic dinosaurs that once roamed southern England 125 million years ago. The researchers delved into the brains and inner ears of two spinosaurs to gain insights into how these creatures interacted with their environment and specialized in hunting fish.

Spinosaurs, characterized by their long crocodile-like jaws and conical teeth, were adept at stalking riverbanks in search of prey, particularly large fish. This behavior distinguished them from other theropods like allosaurs and tyrannosaurs, showcasing a unique adaptation to a semi-aquatic lifestyle.

Through the study, the scientists examined fossil braincases of a baryonyx from Surrey and a ceratosuchops from the Isle of Wight. The reconstruction of these ancient brains and senses aimed to unravel the evolutionary journey of spinosaurs, with their findings presented in the Journal of Anatomy.

Leading the research, PhD student Chris Barker remarked on the intriguing discovery that despite their specialized ecological niche, spinosaurs’ brain structure shared similarities with other large-bodied theropods. This suggests that the ancestors of spinosaurs may have already possessed brain and sensory adaptations suited for fish-catching activities.

Dr. Darren Naish, a contributing author, emphasized the significance of obtaining comprehensive information on sensory abilities from British dinosaurs. He highlighted the use of advanced technology to reveal details about hearing, sense of smell, balance, and other sensory functions in these ancient creatures.

By digitally reconstructing the internal soft tissues of the well-preserved braincases, the researchers uncovered intriguing insights. They observed that the olfactory bulbs, responsible for processing smells, were not highly developed, and the ears were likely attuned to low-frequency sounds. Additionally, parts of the brain related to maintaining stable head movement and focusing on prey appeared less specialized in these early spinosaurs compared to later, more adapted species.

The University of Southampton spokesperson highlighted the innovative nature of the study, showcasing how the ancient brains and sensory organs were enigmatic yet provided valuable information on the evolutionary path of spinosaurs. The research not only deepens our understanding of these prehistoric creatures but also underscores the importance of exploring the intricate connections between anatomy and behavior in extinct species.