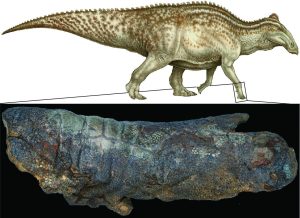

In a recent study published in PLOS ONE, researchers shed light on the preservation of dinosaur fossils with fossilized skin, challenging the notion that such specimens are only formed under exceptional circumstances. Led by Stephanie Drumheller from the University of Tennessee Knoxville, the study focuses on a fossil of an Edmontosaurus discovered in North Dakota.

Traditionally, the term “mummy” has been used to describe dinosaur fossils with preserved skin, a rarity in the field of paleontology. Common belief suggests that rapid burial and protection from scavengers are necessary conditions for skin to fossilize. However, the Edmontosaurus fossil studied by Drumheller and her team unveils a new perspective.

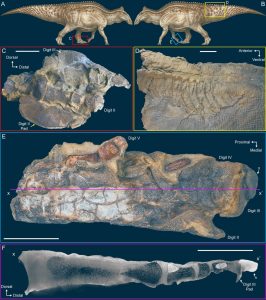

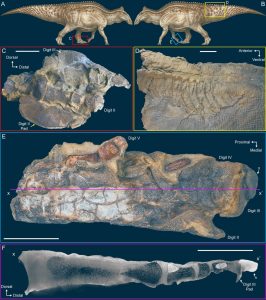

Despite the presence of bite marks from carnivores on the dinosaur’s skin, indicative of scavenging, large patches of desiccated and deflated skin on the limbs and tail were well-preserved. These marks are the first evidence of unhealed carnivore damage on fossil dinosaur skin, hinting that the carcass was exposed to scavengers but managed to undergo mummification.

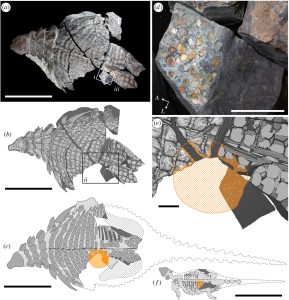

The researchers propose a process termed “desiccation and deflation” to explain the formation of dinosaur mummies under ordinary circumstances. Through the comparison of modern animal carcasses, they suggest that incomplete scavenging can expose the internal tissues of a carcass, leading to the escape of fluids and gases, ultimately allowing the skin to desiccate and drape over the bones before burial and fossilization.

Illustrations accompanying the study depict how incomplete scavenging leads to the drainage of fluids and gases associated with decomposition, preserving the skin and other dermal tissues until fossilization occurs. This insight challenges previous notions that dinosaur mummies are only a result of rapid and exceptional burial conditions.

By understanding the mechanisms behind the formation of dinosaur mummies, paleontologists can improve their collection and interpretation of such rare and informative fossils. Clint Boyd, a Senior Paleontologist at the North Dakota Geological Survey, emphasizes the importance of these findings, highlighting how durable soft tissues like skin can provide valuable insights into interactions with other animals post-mortem.